For at least one direction (across or along the building) the centre of rigidity or resistance is located anywhere beyond the half-way point between the centre of a typical floor plan and the side of the building.

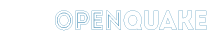

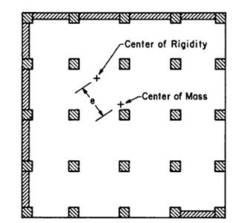

Torsion is created when the centre of mass (CM) and the centre of rigidity or resistance (CR) in the building do not coincide - the distance between these two points is referred to as torsion eccentricity. CM is usually the geometric centre of the floor (in plan). Location of the CR depends on the characteristics of components of lateral load-resisting system (shear walls, moment frames, braced frames, etc.). Torsional effects can develop only in buildings with rigid diaphragms. Also large torsion eccentricities may not lead to torsion irregularity if lateral load-resisting structure normal to the torsion generating structure is widely-spaced in plan and strong.

How torsional effects develop in a building (FEMA 454)

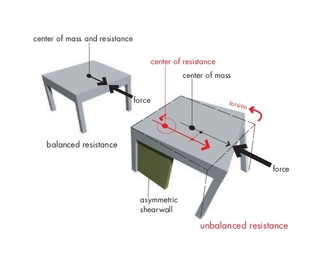

Torsional effects can develop in buildings whose configuration is regular and symmetrical, however stiff structural components such as strairwells or elevator cores are offset with regards to the centre of mass. The photo shows a building in Vina del Mar that was severely damaged in the 1985 Llolleo, Chile earthquake, and the drawing shows its floor plan (FEMA 454)

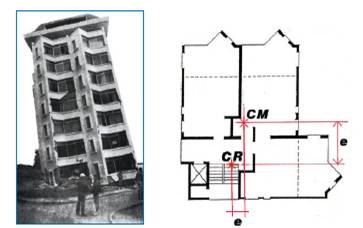

Torsional effects develop in corner buildings or open front buildings, such as shown on the drawing (FEMA 454)

An open front building (fire station), Vancouver, Canada (S. Brzev)

Collapse of the J.C. Penney building in the 1964 Anchorage, USA earthquake was attributed to torsional effects. Shear walls existed mostly along south and west facade. There were no shear walls in the north facade, which was covered by precast concrete panels, and there was a partial shear wall in the east facade. Torsional effects caused collapse of the east wall, and progressive collapse in the south and west walls. The photo shows east facade of the building after the earthquake, and the drawing shows a building plan (Courtesy of the NISEE, University of California, Berkeley, and U.S. National Research Council)

A reinforced concrete frame building under construction was damaged in the 2005 Kashmir earthquake in Pakistan (see Figure 1). Columns in upper storeys suffered severe damage and permanent displacements (Figure 3) due to a decrease in the stiffness at upper storeys; this was caused by concrete block infill walls at the ground floor level. The damage in the columns was aggravated by the presence of a rigid stairwell in one of the corners (see Figure 1) which collapsed (see Figure 3). The stairwell caused torsional effects in the building due to eccentricity between the centre of mass and the centre of resistance (M. Tomazevic)

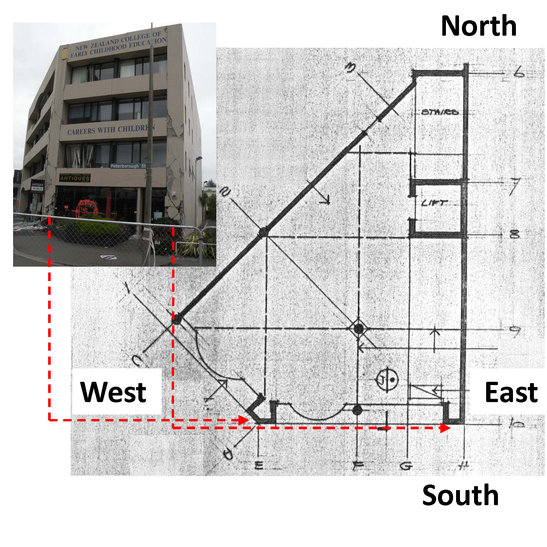

A reinforced concrete building was damaged in the 2011 Christchurch, New Zealand earthquake due to torsional effects. Lateral load resisting system consisted of reinforced concrete shear walls and elevator core along the east and north-west direction and reinforced concrete and masonry columns at the south, as shown on the plan. The damage was most pronounced in reinforced masonry and reinforced concrete columns located at the southern facade of the building, as shown in the photo (J. Centeno)

Building with an open first storey along street corner and walls along other exterior faces collapsed in the 1999 Chi Chi, Taiwan earthquake. The building tilted due to collapse of first storey columns, creating apparent torsional weakness (Courtesy of the NISEE, University of California, Berkeley, photo: J. Moehle)